Empowering women through a non-traditional economic activity: A case study of a female operated trekking company in Ladakh

My research, based on a feminist approach, analyses how a group of women in Ladakh is navigating their gender relations in order to work in the trekking sector, a traditionally male dominated environment. By using a case study of the only all-female run travel company in Ladakh, the research addresses the impact that challenging stereotypes is having for these women. It also studies the impact that a project like this can have in contrast to an income generation program.

The idea came from a personal interest in the role of women in different cultures and how particular activities can shape women’s agency impacting individuals and wider society. Ladakh was chosen as an example of the impact of modernisation and the connection between sustainability and women. Ladakh remained almost totally isolated, until 1962 when a road was built by the Indian Army to link the region with the rest of the country. Then, in 1975, the region was opened up to foreign tourists, and the process of development began. Because this process has happened in a short period of time, it is easy to see the detrimental effect upon community and ecology that progress in Ladakh is having. In this context, women are the ones taking an active role in preserving their culture and looking for alternative incomes.

General overview

Although the importance of women’s empowerment in achieving sustainable development has been increasingly recognised, still most initiatives focus on income-generating projects for poor women in the assumption that the economic empowerment will also bring empowerment to other aspects of their lives. These initiatives are trying to respond to the need of poor women by making relatively small investments in income-generating projects. Often such projects fail because they are motivated by welfare and not development concerns, offering women temporary and part-time employment in traditionally female skills such as knitting and sewing which have limited markets. The question arises as to whether women would be more empowered if they had the option to leave traditionally female-dominated work roles and enter other economic sectors.

Research and fieldwork

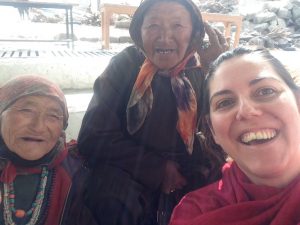

Thanks to the DARG postgraduate travel award I could travel to Leh in September 2016 to conduct my research. Being there for a month and conducting face-to-face in-depth interviews to collect primary data was vital. It was important to carry out the interviews in situ so I could provide an appropriate space for participants to express themselves, as well as give examples of their everyday working lives.

The participants were all trekking guides currently working in the Ladakhi Women’s Travel Company (LWTC). The LWTC is a travel agency owned and operated by Ladakhi women. Local guide Thinlas Chorol founded the LWTC in 2009 to give women in Ladakh the opportunity to participate in the traditionally male-dominated areas of trekking and mountain climbing. The LWTC is the only all-female trekking agency in Ladakh, with women involved in organising and running treks, which also serves as a unique example to the rest of women in Ladakh.

In total, I conducted eleven audio-recorded interviews. These were conducted in English, which meant no translator was necessary, and therefore without anyone else present, ensuring the anonymity of participants.

Findings and Discussion

The results have shown different impacts in diverse areas and the complexity of how these women are negotiating their role between their public and private lives. By working in the mountaineering sector, they have achieved financial independence and have learnt about other cultures, improving their ability to communicate with others and bringing some self-efficacy. As well as gaining confidence from learning English and meeting foreigners, many participants seem to feel empowered by and proud of working in a role traditionally filled by men. However, in the private sphere, women are still expected to fulfil their role of carer and their household responsibilities, resulting in a double burden when they join the labour market. The research has also shown that these women are still not prepared to profoundly challenge the socio-cultural norms and expectations imposed upon them.

A high agency of decision-making was visible in their independence in controlling economic resources, which in turn shows a high level of economic empowerment. However, their participation in the village councils seems to be extremely low, which shows how unrepresented and unheard they are in the decision-making structures. These women have not yet gained the necessary confidence to insist on their voices being heard in the political sphere.

The findings demonstrate that projects focusing only on economic empowerment ignore other vital aspects of women’s empowerment, allowing social and patriarchal norms to go unchallenged and continue to limit women’s lives. Freeing women from these constraints and unlocking their potential should be considered a priority in future initiatives.